Sugar and spice and all things nice, that’s what little girls are made of

A little less than 4 weeks ago, I had my second child, a daughter. I am over the moon to have her, of course (although all the comments about how wonderful a “pigeon pair” is or how I “can stop now” got old fast and made me extremely defensive of the imaginary little boy she might have been) and yes, I confess I have already been shopping for dresses and added butterflies to her bedroom wall. But she’s less than a month old, not expressing preferences for what to wear or play with or do, and frankly until nappy change time she’s no different to a newborn boy. I want to keep it somewhat gender-neutral and treat her the same as our son, but at the same time, I’m afraid of the new set of challenges that I feel like she’ll face that he won’t. Somehow we now live in a world where right from birth, raising a child means picking a side in any number of gender debates, navigating a whole politics of parenting, and trying to get the adults around you to be a part of that.

It starts with names. Now, I could write a separate blog post about names, because I’m one of those people who has a whole rule list about naming children and really wouldn’t object if it was enforced on others somehow. But rather than get in to the whole list, I’ll stick to talking girls and boys: I like gendered names. I like my girl’s names on girls and I like my boy’s names to stay on boys. I don’t object to androgynous names per se, I wouldn’t see them banned or anything. I object to how they never started out androgynous and they very rarely stay androgynous. In 1915, a baby called Quinn was 99.9% likely to be a boy; in 2010 it was 51% girls – pretty much the definition of a unisex name. But just two years later in 2012 86% of little Quinns were female (I think Glee had a part to play in all of this). That’s an extremely quick evolution, but this list shows just how many names that were considered “unisex” at some point are now firmly in the girl’s camp (when was the last time you met a male Allison?). And it’s pretty rare for it to go the other way, although boy-unisex-boy again does happen occasionally. So, what bothers me about people who call their daughters Ryan or Maxwell is that they’re rarely calling their sons Abigail or Lucy. They want a “strong” name for their little girl, they want her resume to make it to the interview pile, and they know that giving their son a “girly” name is likely to have him embarrassed or beaten up a lot at school. And now the boy’s list is getting shorter and consequently a lot of classic boys names seem boring and overused. So I stuck to a feminine name for my little girl, one that historically began as a girl’s name and stayed that way. The plus side about this issue in the “to gender or not to gender” question is that there’s only two people who have to agree. Announce the name at birth and 99% of people will go ahead and call the kid your chosen name.

So then the baby is born and named, and now the issue is clothes. Because let’s face it, all a newborn does is eat, sleep and poop, so there’s nothing much to do except feed them, dress them (frequently, if they’re a spewer or a poonami baby) and then look at them or show them off to your friends. In the early days, a lot of time is spent focusing on what the kid looks like and everybody who likes shopping loves shopping for tiny baby clothes. I was never much of a “girly” girl, and so I always thought I would get stuck if I had a daughter who was. I don’t know what I’m going to do when she’s a preschooler and wants to paint her nails, because I don’t own a single bottle of nail varnish. When she’s old enough to tell me what she wants to wear, it might be tutus and sparkly tops, dresses and frills, in which case I guess that’s what we’ll buy. But I always wanted to avoid that stuff in the early years. Then I noticed the pink invasion. Pink would be fine if it was treated the same as blue is for boys – if it was one, albeit gendered, option. We were given blue clothes when our son was born. We were also given clothes in green, red, brown, black, white. We were given obvious “boy’s clothes”, collared shirts or outfits with trucks on them, things proclaiming how great Dad is and all that. They weren’t all blue. In fact, looking at his wardrobe now, less than a third of it is blue, and I never made a conscious effort to avoid it. Pink is a different story. My dislike for pink grew from pink toys (we’ll get to that) and was a little like going out for dinner with single friends on Valentine’s Day – a protest to something much more than a genuine desire to spend a fortune on restaurant food. I don’t actually hate the colour pink and I think some pink clothes can be delicate and beautiful, but I wanted the same variety that my son got and I was indignant that the shops would not offer it to me. I objected passionately to this one facet of gendering (pink), while going along with others (dresses etc) and I appeared completely irrational as a result. I found myself declaring that if we ever had a daughter, our house would be a pink-free zone. Ha. Well, I’m yet to personally purchase anything pink for her, sure. I’ve gone out of my way to find blue and white and red dresses, picked up a few Minnie Mouse bargains or navy clothes with hearts on them, and of course utilised the wardrobe full of clothes we still had from our first baby. But if you have people who love you and want to celebrate with you, and those people buy gifts, and you’re not a horrible person who throws out the generous gestures of people you care about, your house will not be a pink-free zone. 100% of people who gave us a present bought something pink. Marketing won this round.

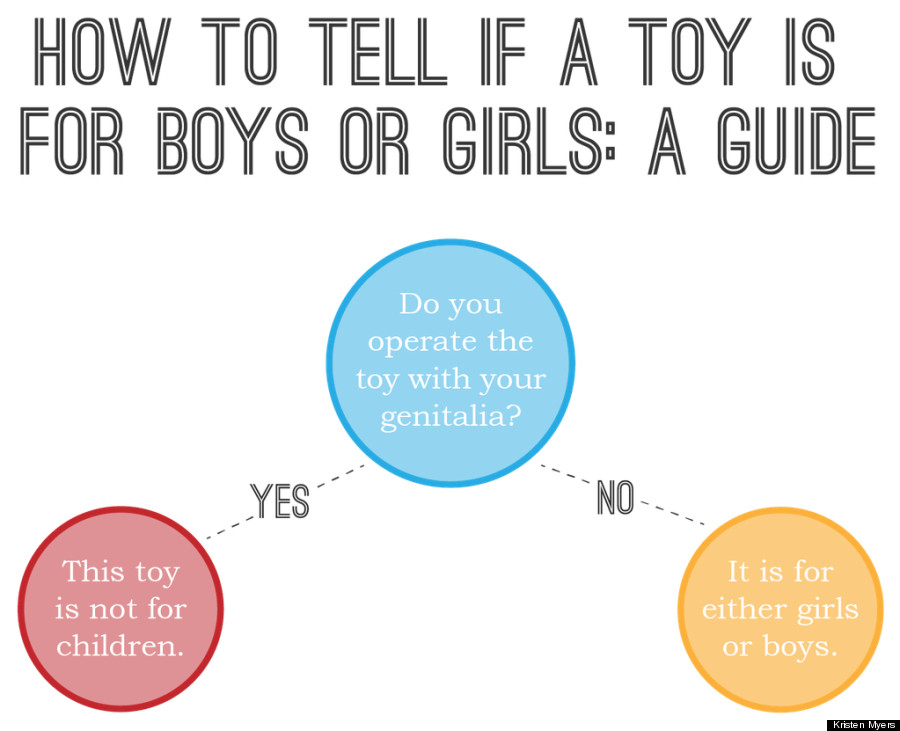

The next battle that I’m gearing up to fight is the one that started the anti-pink sentiment in the first place, and the one that leaves me most confused, anxious and envious of all-boy mums. Toys. Now, I’ve always been against the idea of limiting what children can or “should” play with based on what’s between their legs. I’m a fan of this info graphic:

So I’ll preface this by saying that I’m not talking about withholding dolls from my daughter or anything like that (my son has two, so that’d be hard to do anyway). I always thought the idea of “girl” toys and “boy” toys was a bit silly, because I have plenty of memories of my brother’s teddy bears sitting alongside my cabbage patch kid while we played mums and dads or schools or whatever. And I’m not saying that there’s anything wrong with a girl who picks the fairy wings over the fireman’s hat in her dress-up box. No, what bothers me is this:

Toys that were never traditionally considered “boy” toys in the first place are now being made in a “girl” version. Sure, chuck some pink and purple blocks in the mixed box of Lego, add some variety and appeal to the kids for whom pink is a favourite colour, great idea – oh wait, if I want the pink ones I need to buy a whole different set? This is marketing ordinary, creative toys, often toys designed for preschoolers and toddlers, in such a way as to exclude boys and simultaneously imply that girls shouldn’t play with the non-pink version. When I was a kid, it’s not like all us girls were running around going “oh, I’d love to play with that if only there was a girl version”. This stuff wasn’t created to meet a need in the market, it was created to make a need, so that parents like me who already have a red cozy coupe for our son might feel the need to buy another for our daughter. And it makes me oh so angry, that businesses want my child to feel different, to be limited, to turn “pretty” and “feminine” into words that decide whether something is acceptable for her or not, so that they can make more money from her.

So I’m hurtling along, flying toward the anti-gendering, feminist angry non-consumer and then I hit… This piece about a new “average proportion” barbie-style doll. Oh Barbie. How you have become the focus of all our body image problems. I’m thinking “oh yes, I’ll be avoiding Barbies at all costs. Even worse are those Bratz dolls. Not a role model I want for my child.” But I don’t really know anyone who aspired to look like Barbie in the first place. Have her wardrobe, perhaps. Barbie is a fashion doll, her figure was designed so that all the clothes she wore would have shape to them despite folds or seams or elastic waists, not so that she’d look realistic naked. But should we be encouraging fashion dolls in the first place, if they start making young girls obsess about clothing and slim figures? But really, dressing and undressing gets boring after a while, what games do kids play with Barbie anyhow? I know women who have fond memories of Car Crash Barbie, Earthquake Barbie, Ghost Hunter Barbie, Serial Killer Ken, and of course, Lesbian Sex Barbie. But can’t they do that with a different doll, what do they need Barbies for? And on it goes. You can overthink it all until you go crazy. Don’t get me started on Disney. There’s the Big Corporation taking advantage of little girls, the Pink and Sparkly obsession, the 1950s gender roles; they are perhaps the biggest offender of my Girl Toy problems. And then there’s my own absolute love of Disney movies. Am I a sell-out if Bambi pyjamas are ok but pink Lego isn’t?

What ever happened to toys just being toys?

So that’s it. My 4 week insight into what it’s like to have a daughter: exhausting. But she’s asleep beside me as I’m typing this and I realise that the reason I care about all of this, the reason I’ll keep overthinking it and not just give in to whatever is easiest, is that she’s perfect. She’s worth being exhausted for.